How to use the TSP’s G Fund in Bear Markets

In light of how volatile the markets have become this year, many federal employees have looked to the G fund for safe refuge. But the G fund serves a greater purpose than simply reducing the volatility in your TSP.

The G fund is like a savings account on steroids, figuratively speaking. Its returns are not great but are much better than your bank’s savings accounts. When building a well-diversified portfolio, you need to have “not-great-returning” investments as well as ones that do provide you with healthy returns over time.

This applies to all age groups. A healthy balance sheet starts with having a cash position, either in your investment accounts or in your banks, so that you have cash to cover your needs for a short period of time. Beyond that will depend on the specifics of your life.

The ratios between the kinds of investments in your portfolio will differ with each family, based on various factors including but not limited to economic indicators, market cycles, lifestyle choices, timelines, goals, tolerance for risk, need for risk, health expenses, and many others.

It’s critical that as a federal employee you understand the G fund and its role in relation to the overall portfolio that you’re building. Incorrect use can lead to a portfolio that does not perform as you need it to in order to maintain financial independence.

Cash is king

If you’ve seen any number of our articles or videos, then you know that we’re not advocates of trying to time and outperform the markets. The markets are a tool with which you can grow your wealth to help you accomplish the goals you’ve set for yourself.

Ergo, picking hot stocks is out, which then redirects one’s investment strategy to the most important fundamental factor: asset allocation. This is simply the mix of investments of which your portfolio is comprised.

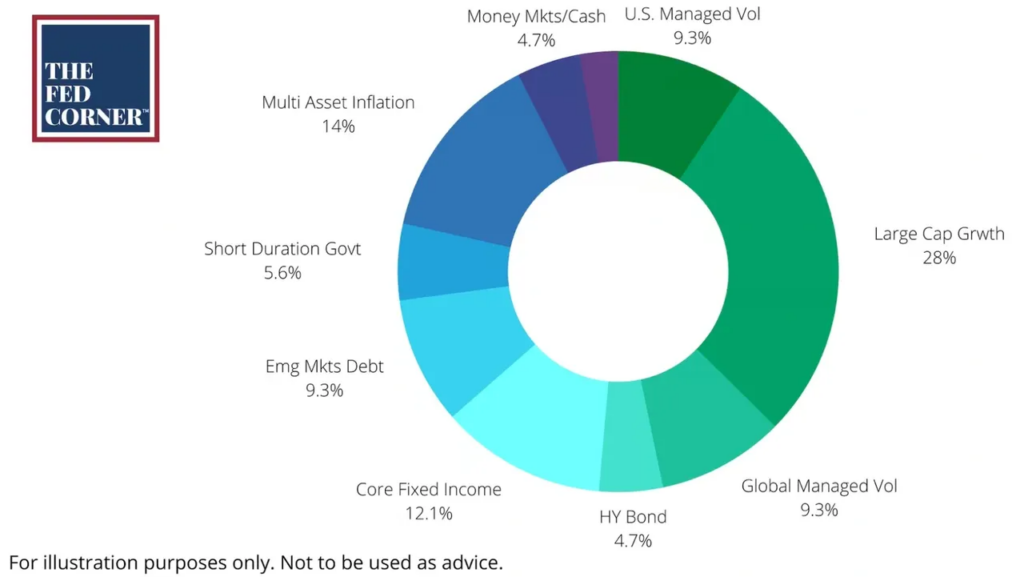

Some parts of it will be invested more aggressively to grow your money for the future. Other parts will be conservative to help you meet your more immediate needs. The rest is everything in between. Here’s an example:

When we think about our needs on a shorter-term basis, those are most commonly met with your portfolio by means of conservative investments, and sometimes cash. Your portfolio’s asset allocation should shift over time, being influenced by the various factors mentioned above. Sometimes holding more cash and/or G fund is better. Other times it’s not.

For example, if you’re still earning an income, the cash and conservative portion of your portfolio can be reduced. The need for tapping your saved capital is less. However, if you’re planning to renovate your kitchen and master bathroom, then perhaps it’s appropriate to hold a heavier conservative position despite the fact that you may still be working—unless you choose to utilize a Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC) to fund the project, which may have deductible interest if you’re making improvements to your primary home. This way you can keep your money working for you while also having the home renovation you want.

You see, there is no blanket answer in determining how much of a cash position to hold in your portfolio. It’s formulaic at best. The answer must be driven by the factors that will be influencing your choices. Much of financial planning must take this approach to be successful.

General Rules

Despite a family’s asset allocation being highly personalized, there are some general rules by which investors should abide if they have not yet put together their formalized plan.

Under normal market conditions, families with only one income for their household should be looking at roughly 4-6 months of cash or money market funds if they’re still earning an income. Dual income households can reduce that down to about 3 to 4 months, provided both spouses are still working and earning an income.

The reason for this is because the economy and the markets can become volatile in the short term, as demonstrated by this year, and you don’t want to be tapping portfolios if they’ve suffered from declined values in the event that you need cash.

This general basis should give you a good starting point in determining how much of a cash position you should be holding. From here, you should determine what your upcoming expenses outside of “normal” may be, and how best to fund them. Sometimes it’s cash, other times it’s leverage, philanthropic goals may be met with investments instead of cash; so it truly depends.

The amount of cash you should hold goes up when markets get rough, because when volatility returns the probability of markets being lower when you need cash is higher, so therefore you hedge against that risk, by holding a more cash.

If you’re no longer earning an income and your pension, Social Security, and portfolio must now support you, the current economic environment would call for closer to 12 months’ worth of expenses, and possibly more.

Beware of TSP Distribution Rules

The G fund offers slightly better returns than a high-yielding savings account, so you can certainly use the G fund as your cash position, so long as you understand how TSP withdrawals work. You must remember that the TSP does not allow you to withdraw only from the G fund unless the G fund is the only investment in which you are invested.

This could make your strategy of holding cash for use in volatile markets useless, as selling the other TSP funds when markets have fallen makes your losses permanent unless you reinvest equally as aggressive. This is known as sequence-of-returns risk.

Unfortunately, the TSP does not currently have a solution for this, and the challenge with holding only the G fund in your portfolio is that your money will not grow fast enough to support the rest of your life.

One solution is to use the TSP merely as the G Fund custodian and have another custodian with less restrictions for the rest of your portfolio. That way, whenever you need the cash, the TSP only has one fund from which to sell–the G Fund. This has been successful for many of our clients.

The other alternative, especially for federal employees still in service, is to have the cash portion of their portfolio housed inside a savings account with their bank, and perhaps utilize the G fund in their TSP solely as a volatility reducer. It does this well, at the cost of not growing once the markets rebound.

A Bloomberg report shows us that the equity markets have historically bottomed an average of 5-6 months ahead of the economy and the economic indicators. This could mean that the markets are recovering for months before you see real signs of an improving economy.

This is why most investors are rarely ever able to get back into stock market again at an opportune moment after a decline. That moment is generally in the midst of a still degrading economy, and why the strongest returns in the markets have been offered during bear markets. So using the G Fund as a volatility reducer can be a double-edged sword.

Remember, bear markets are defined by market performance, while economic news, such as recessionary pressure, is based on GDP.

The G fund will have missed out on all of that potentially slow but sure recovery. The slower the recovery is, the more challenging it is to realize the market cycle has flipped. This risk can mean that you locked in your losses, especially if you moved to the G fund after sustaining losses.

This is why the importance of planning cannot be overlooked. It allows you to develop a strategy around your needs, wants, and desires, so that you’re able to live the life you want to live despite how the markets are preforming.

If you don’t have a plan, take the time to plan this year. If you do have one, now is the time to review what you have to help make sure you’re still on track, because it’s not just your money, it’s your future.

Want help? Just send us a message.